Brad Brown began working at the Burpee Museum shortly after graduating from Northern Illinois University in 2009 with a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Geology. He has assisted with multiple Burpee field seasons in Utah, Wyoming, and Montana including the excavation of Homer, Burpee’s “teenaged” Triceratops.

In Montana’s eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains stand ancient weathered hills above gently rolling plains. Within these hills numerous fossils await their discovery by some intrepid, wide-brim hat wearing paleontologist. Animals preserved in the mud that entombed them around 75 million years ago had no way of knowing the significance a band of bipedal, relatively hairless mammals would find in them. This location, a section of the Two Medicine Formation, has been a hotspot of diverse fossil discoveries for over 30 years despite its sleepy surroundings.

Morning view from my tent. The teepee was used by friends passing through for a night or anyone whose tent was damaged by the occasionally raucous wind.

The Two Medicine Formation became a consistent site of paleontological study beginning in the late 1970s when the first known North American dinosaur egg fossils were reported. Montana paleontologist, Jack Horner, with collaborator, Bob Makela, and a group of Princeton students prospected the Two Medicine, and their years of work identified more than mere egg fragments. They found numerous egg nests, some containing embryos. Laid by the hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) Maiasaura, the Montana nesting sites have provided much insight into dinosaur anatomy, ontogeny (changes through maturation), and parenting behavior. The Maiasaura bone bed can be traced across numerous hill exposures including Camp Makela where the crew spends their evenings dining and refining their research. Horner and his students have estimated that over 10,000 Maiasaura skeletons were deposited at the location (though many have long eroded away) leading them to believe that the animals died during a catastrophic flooding event.

Another Two Medicine fossil site of interest, dubbed Egg Mountain, has provided a unique window into the deep past. Named for the original attractant to the site, Egg Mountain has produced many fossils of eggshell from dinosaurs, birds, and crocodiles. Dr. David Varricchio of Montana State University has been working at Egg Mountain for the past five summers and has unearthed an assortment of small Late Cretaceous creatures, some of which are thought to correlate with the site’s eggshell. Dinosaurs present at the site include a possible burrowing animal called Orodromeus, as well as the bird-like theropod, Troodon. Teeth of hadrosaurs and the theropods Saurornitholestes and Daspletosaurus have also been found. Non dinosaurians from lizards to mammals, both placental (such as rabbits, mice, etc) and non-placental (marsupials, monotremes, and an extinct group, multituberculates) have been some of the most complete specimens from the site. Trace fossils are also prevalent at Egg Mountain. Backfilled insect burrows and pupa chambers as well as pupa cases still showing silk weave patterns are among the most abundant signs of prehistoric life, representing numerous beetle and wasp species. Such fossils provide important details about the paleoenvironment and are an interesting topic of research for ichnologist and author, Dr. Tony Martin, of Emory University.

Egg Mountain is a somewhat atypical fossil locale because it represents a terrestrial setting as opposed to the more watery fluvial and lacustrine settings which tend to provide reliable opportunities for sediment accumulation, therefore, fossilization. The site is currently believed to preserve a natural levee along the bank of an ancient river. The prevailing sediment would have been mud and soil which, over great swaths of time, hardened into a gray mudstone with blocky carbonate nodules. Carbonate rock can indicate to a geologist that the area was perhaps a shallow marine environment, but this is no marine limestone. The micrite found at Egg Mountain is derived from carbonate rock which eroded from a marine Paleozoic deposit to the west that was uplifted during the early rise of the Rocky Mountains. Rivers carried the carbonate in solution, flooded periodically, and the carbonate material percolated into the Cretaceous soil. During dry seasons, water in the soil evaporated leaving behind nodules of solid carbonate.

Originally so many bones of Orodromeus juveniles and adults were found at the site that it was thought to be an Orodromeus nesting site. The identification of embryos as Orodromeus seemed to confirm that, however, after more Troodon specimens were found and studied Dr. Varricchio realized that the embryos were originally misidentified and are actually Troodon. It is believed that Orodromeus remains may represent prey items of brooding Troodon parents. Dr. Varricchio’s team has uncovered a significant clutch of two dozen elongate ovoid eggs within a bowl shaped trace of a nest constructed by and fitting the body size of Troodon which is on display at Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, MT. The eggshell of Troodon is very smooth and closely resembles the texture of bird eggs. A bumpier type of dinosaur eggshell is thought to represent a dromaeosaur (the group including Velociraptor), though no skeletal material associated with a clutch of bumpy eggs has yet been found. Pieces of crocodile teeth and egg shell are found at the site, but again, no associated skeletons or nests have surfaced. A handful of very complete mammal and lizard specimens have been collected from Egg Mountain and continue to draw interest from experts and collaborators such as Dr. Gregory Wilson of the University of Washington. The Two Medicine Formation is possibly the host locale of the best preserved Late Cretaceous mammals in North America.

As a prospective graduate student hoping to study paleontology, I contacted Dr. Varricchio about his research at Montana State University. After keeping in touch over the winter months we met in person this past March at Burpee Museum’s annual PaleoFest event. We talked about field work, as many paleo folk start getting antsy in spring, and Dave invited me to volunteer with his crew. I was only able to stay for one week, but that was enough to get an idea of how the site operates and what should be expected of it.

Orodromeus femur in micrite. Working the micrite requires breaking large rocks into small rocks, so bones are often split among a slab and counter slab.

Egg Mountain is a rather flat rectangular site atop a hill, setup in such a way to simplify mapping. The crew is spread across a grid and works their section down from the surface until they reach an established lower horizon. The mudstone requires occasional jack hammering so that the crew can work through the rubble with brushes and awls keeping their eyes sharply tuned to spot very small bone and egg fragments. In the afternoon of my first day at Egg Mountain I ‘worked the line’ until I found something that did not look quite like mudstone. Being new to the operation, I asked, “Dave, do my eyes deceive me? Is this bone?” Indeed, it was part of a tibia to an Orodromeus. Further excavation uncovered a femur, a vertebra, a possible fibula. Then, in carbonate micrite, there was another femur, more vertebrae, and a few toe bones. On my last day I circled around to the original material found in mudstone and ran into yet another femur along with a radius and an ulna. Three total femora were present indicating that there were two animals! Normally, the site’s student and volunteer workers hunch over scads of crumbly mudstone for 3-5 weeks finding mostly trace fossils, isolated bones, and eggshell fragments barely visible to the naked eye, mere stains on the rock compared with the large Maiasaura bones that lay just a mile away. Over the course of the week I realized that I was not having the typical Egg Mountain experience. To find multiple dinosaur bones every day for a week was a rare treat that I will not soon forget!

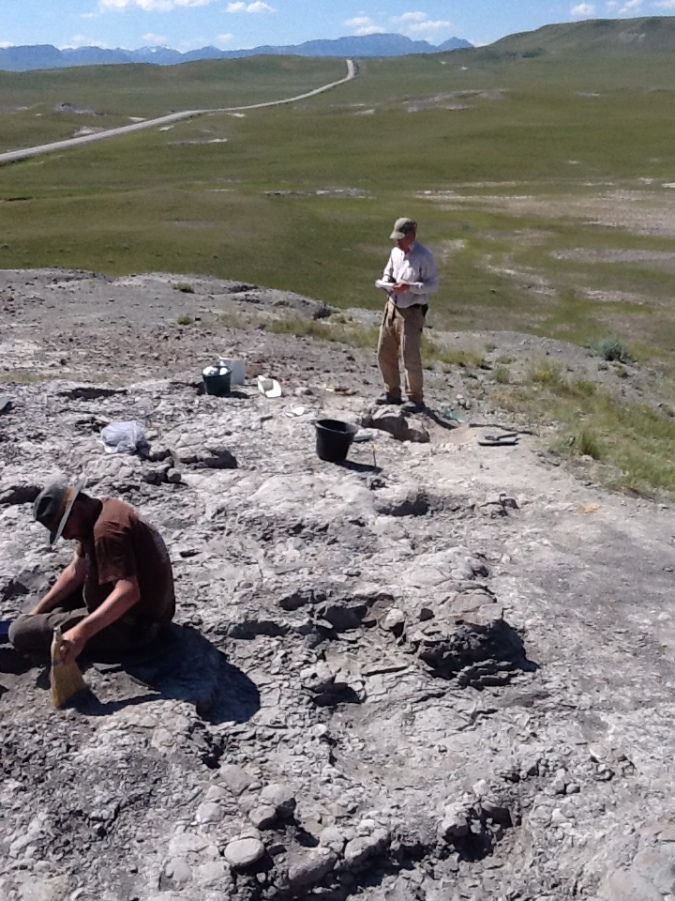

Dave maps the orientation of Orodromeus bones. The bucket in front of him contains the day’s finds wrapped in paper towel and aluminum foil. In the foreground volunteer, Ulf Schyldt, of Stockholm, Sweden sweeps his section clean of rubble while seeking tiny ancient treasures.

Science is a beautiful and humbling cohesion of the observations, experiences, and testable ideas that humanity has encountered and manipulated over many centuries. I owe much of my experience in the scientific world to Burpee Museum’s long running expedition program. I had never found a dinosaur bone until I went to Montana with a class run by Highland Community College professor, Steve Simpson, in collaboration with Burpee. I found myself returning to spend as many summer breaks as I could in the Hell Creek Formation of the eastern Montana badlands. I was privileged to find myself in Montana the summer that Homer was discovered. The following year I was one of many intrigued individuals who helped uncover the expansive juvenile Triceratops bone bed where Homer and two of his compatriots were laid down. After years of guided experience with Scott Williams and Burpee staff, I am glad to have taken my lessons learned and applied them to a new dig site. Working with diverse groups of people and seeing fossils unseen for ages provides new perspectives and has helped me continue to build upon each experience, finding that science is not just a subject of study or an accumulation of facts and numbers, but a way of life that is shared worldwide.

Stay tuned to No Stone Unturned for more news and stories inspired by the Burpee Museum of Natural History.

For more information about Tony Martin’s research and why insect fossils provide a better understanding of dinosaurs, follow his blog Life Traces of the Georgia Coast and pick up his book Dinosaurs Without Bones, in stores now!